Kosmosest #15: An Interstellar Voyage

August 20, 1977. The first of the twin Voyager spacecraft launched to space with a unique mission.

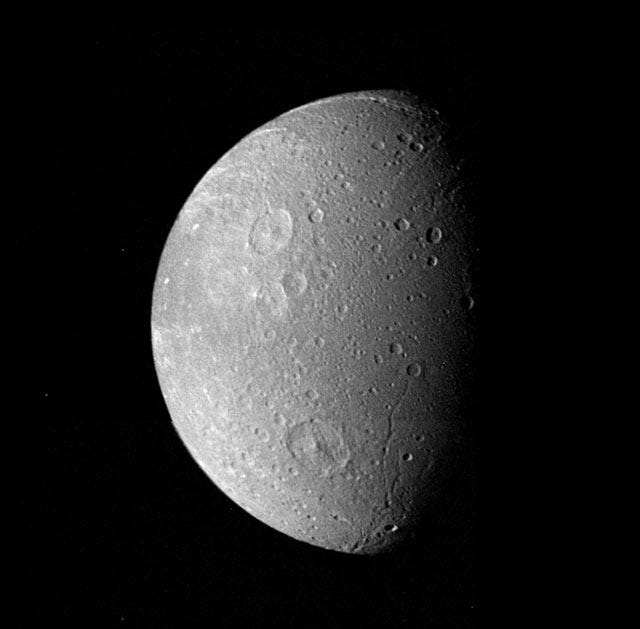

Voyagers were designed to conduct close-up studies of Jupiter and Saturn, and the largest moons of the two planets. Voyager 2 also became the first and so far the only spacecraft to ever fly by the outermost Solar System planets, Uranus and Neptune.

But once these scientific goals were ticked off? Go as far as you can, buddy.

This is a Kosmosest newsletter issue on the Voyager spacecraft.

Still in touch

In July 2023, NASA re-established contact with interstellar Voyager 2 probe after a blackout. Voyager 2, one of the only two spacecraft to reach interstellar space, lost communication due to an accidental antenna misalignment on July 28. A set of commands sent to the spacecraft caused its antenna to be slightly shifted from its intended orientation towards Earth, disrupting Voyager 2's ability to link with Earth. On August 4, however, the Deep Space Network facility in Australia successfully reoriented the spacecraft’s antenna, allowing communication to be reestablished.

The spacecraft resumed sending science and telemetry data from 19.9 billion kilometers (12.4 billion miles) away, functioning as expected on its trajectory. Voyager 2's twin, Voyager 1, is also operational at about 15 billion miles away. The Voyagers launched in 1977 and engineering modifications have extended their functionality (despite their nuclear generators losing power) with data collection now expected until at least 2026.

Tour of the Solar System

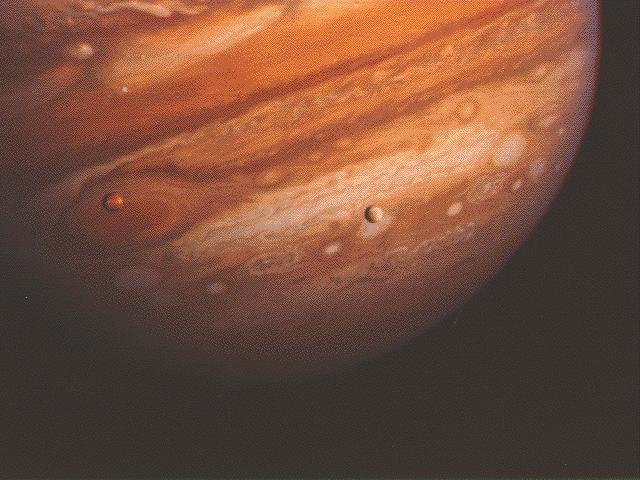

Voyager 1 (launched September 5, 1977) visited Jupiter in 1979 and Saturn in 1980.

Voyager 2 (launched August 20, 1977) visited Jupiter in 1979, Saturn in 1981 and Uranus in 1986 before making its closest approach to Neptune in 1989.

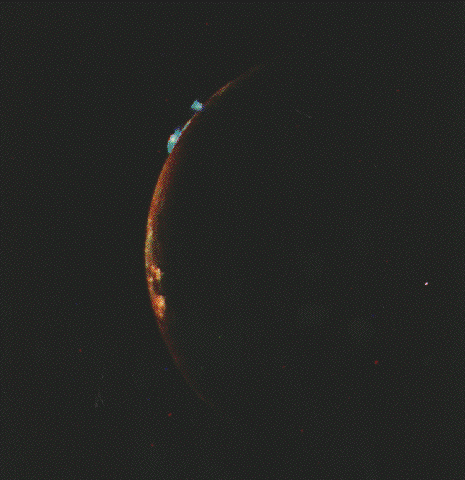

Uranus and its moons

After years of travel, Voyager 2 embarked on an encounter with Uranus, the enigmatic seventh planet in the depths of our solar expanse. It radioed thousands of images and a treasure trove of scientific data on the planet, its moons, rings, atmosphere, interior and the magnetic environment surrounding Uranus.

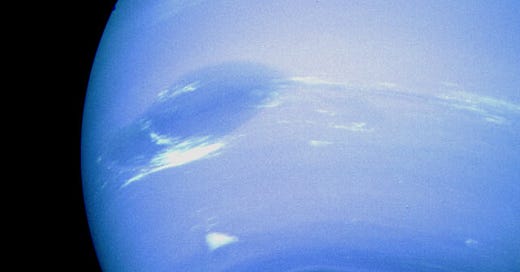

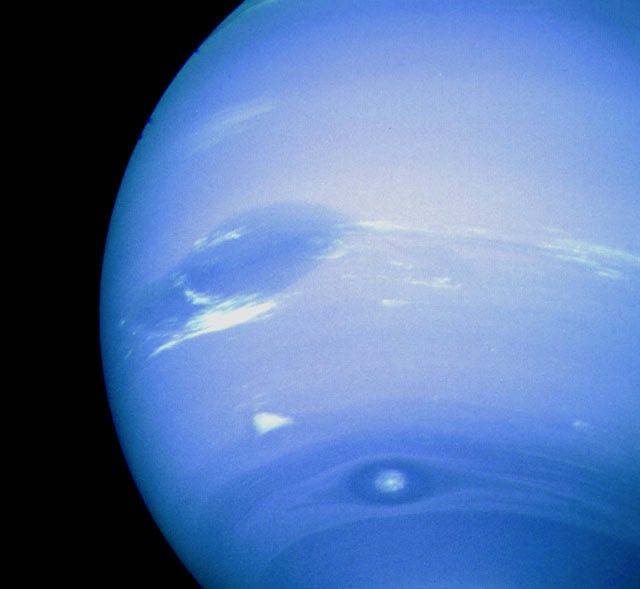

Neptune

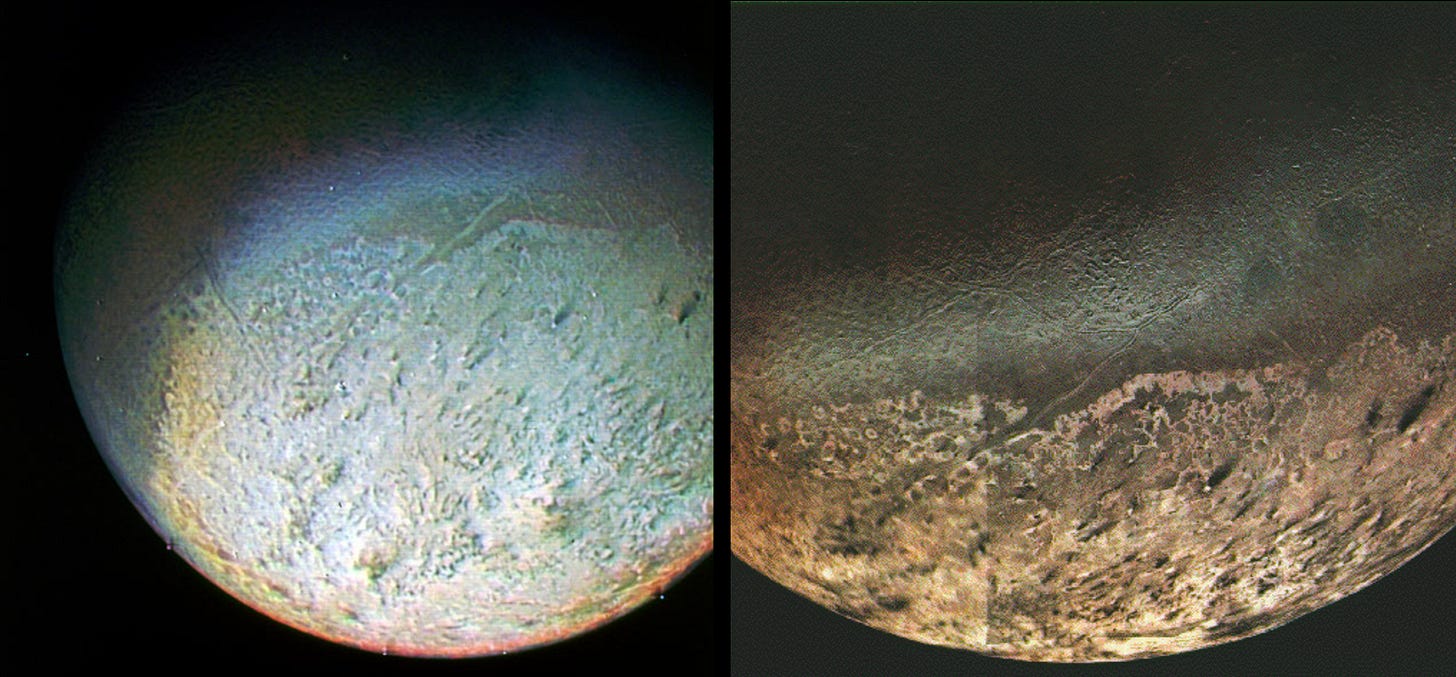

Voyager 2 observed its last planetary target in 1989, passing Neptune’s north pole 12 years after leaving Earth (about 4,950 kilometers or 3,000 miles at the closest approach). The spacecraft also flew by Neptune’s largest moon, Triton; about 40,000 kilometers (25,000 miles) away.

Credit of the images: NASA / JPL-Caltech

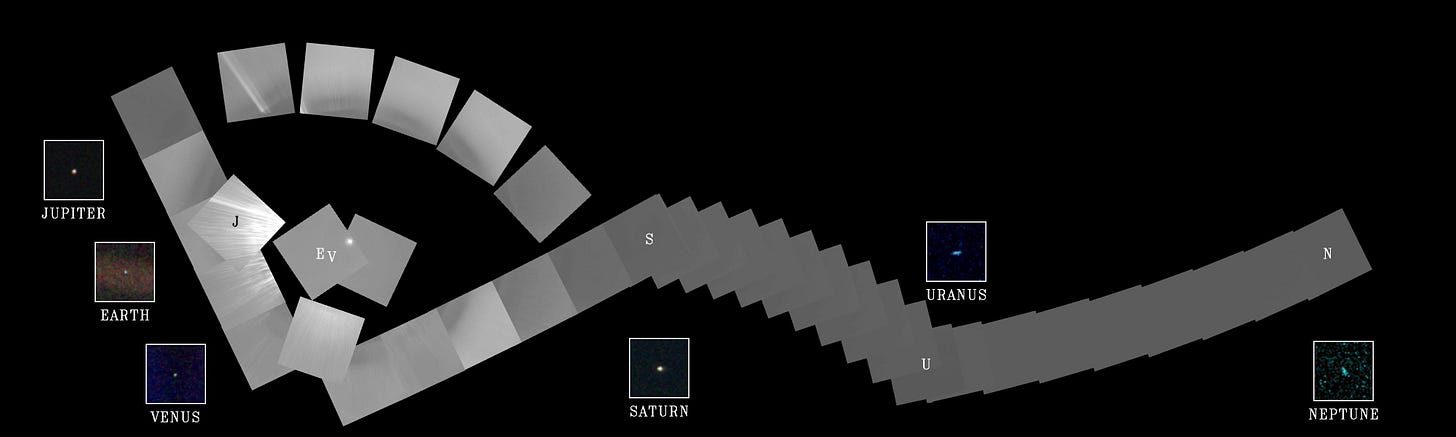

Solar System Portrait and the most distant photograph ever taken of Earth

In February 1990, Voyager 1 was parting with the planets. Astronomer Carl Sagan requested the spacecraft to give the Solar System a last look. It acquired 60 frames for a mosaic from a distance of more than 6.4 billion kilometers (4 billion miles) from Earth and about 32 degrees above the ecliptic. Earth appeared as a mere point of light from Voyager's great distance, inspiring the famed 'Pale Blue Dot' monologue by Sagan.

Carrying the time capsule

Less than a year before NASA’s Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft were scheduled for takeoff, astronomers Carl Sagan & Frank Drake received an intriguing proposal: would they be interested in crafting a message to alien civilizations to accompany Voyager on its interstellar journey?

How To Make A Golden Record (Science Friday):

Over the next 9 months, Sagan, Drake, and a small team of scientists and artists with Ann Druyan as the Creative Director, scrambled to compile a unique document— part time capsule, part interstellar greeting—to send to the stars. The Golden Record was born.

The contents of the records were chosen to embody a message representative of humanity. Each Golden Record contains 117 pictures to convey life on Earth and humanity’s knowledge—images of people doing various activities and a variety of plants and animals, scenes from around the world, and drawings and images that convey information about our solar system. There are also greetings in 54 different human languages and greetings from humpback whales. Finally, there is a selection of sounds from Earth, ranging from storms to noises such as trains, airplane and rocket take-offs.

The symbols on the cover

The team created instructions for the use of the record, and a way to describe the Earth’s location in the galaxy in a way that extraterrestrials might understand. These make up the symbols on the cover.

Diagram of the Record's Placement: This shows the location of the record on the spacecraft, with respect to the Sun and the pulsar PSR 1919+21. The pulsar's radio emissions were used as a kind of celestial time marker.

Binary Numbers: This sequence of binary numbers (0s and 1s) represents the numbers 1 to 10 in binary code. It's meant to introduce the concept of counting and arithmetic in a universal way.

Chemical Formula of the Hydrogen Molecule (H₂): This represents the element hydrogen, which is the most abundant element in the universe and is used as a reference to indicate the composition of other elements.

A Curved Arrow and Solids Representing Vibrations and Sounds: This symbol is used to explain how to decode the audio signals on the record. The curved arrow indicates the direction to play the record, and the various diagrams represent vibrations and sound waves.

Diagram of the Pulsar PSR 1919+21: This graph represents the radio emissions of the pulsar PSR 1919+21, which was used as a kind of cosmic timekeeper in the hopes that it could be used to locate the origin of the message.

Diagram of the Hydrogen Atom and Its Transitions: This diagram illustrates the energy levels and transitions of a hydrogen atom, which is fundamental to understanding the physical universe and the behavior of matter.

Choosing the contents of a record to embody a message representative of humanity is a task which continues to inspire research and reflection, and bridge science and social studies. See e.g. "Voyager Golden Records, 40 Years Later: Real Audience Was Always Here on Earth," written by Jason Wright in 2017.

“Whenever I'm down,” says Druyan, the Creative Director, “I'm thinking: And still they move […]” in an NPR interview in 2010.

Thanks for reading!

If you’d like to show your support for educational content:

Share this newsletter with others: spread the word! You can use your preferred social media platform.

Like the posts and leave comments if you found the content useful.

Became a paid subscriber.

Or buy the author a coffee:

https://ko-fi.com/kosmosest

A big thanks to each person who has subscribed to this newsletter, and gives me a platform to share what we know (and don’t know) about the universe.